EDICOLA

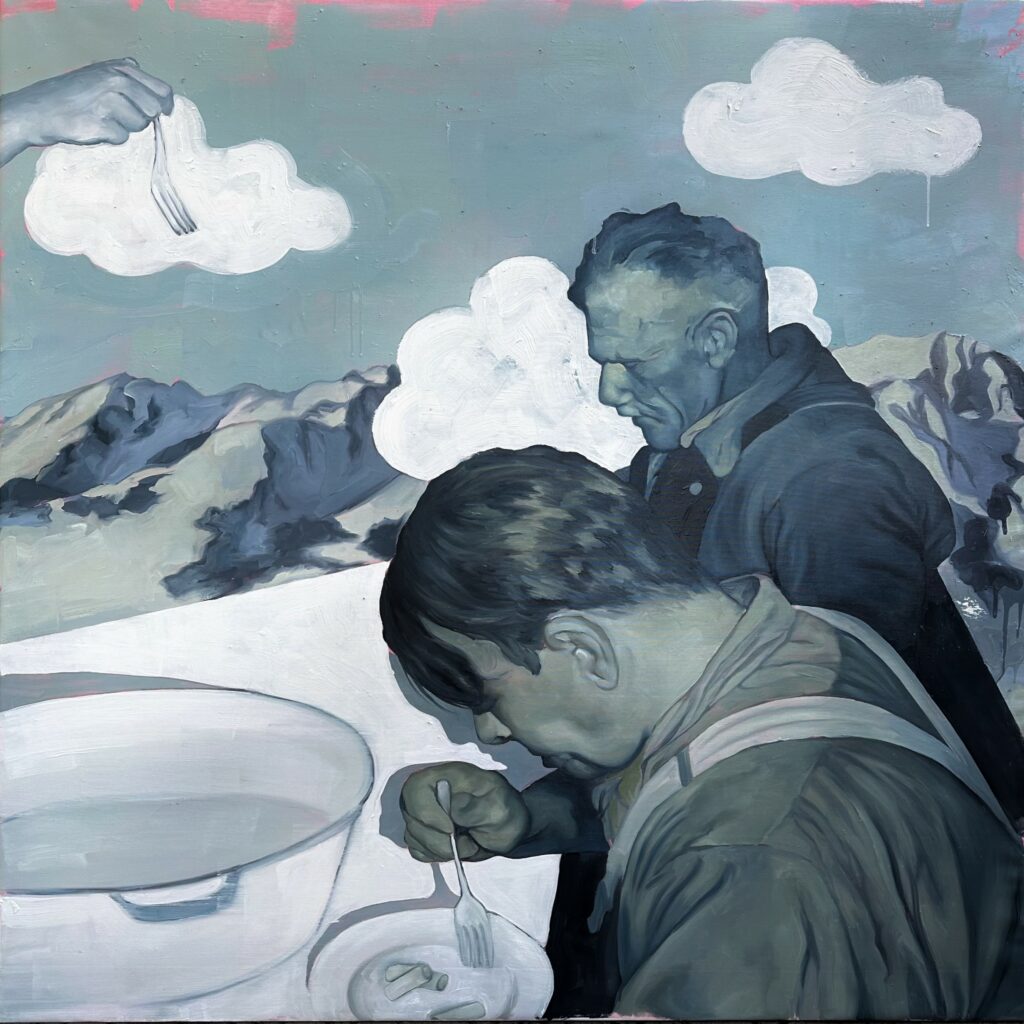

The painting is striking for its ability to blend a traditional pictorial language that remains suspended between document and dream, a blurred realism that becomes a surreal and alienating memory. The two figures, bent over and gathered together, seem immersed in an everyday gesture – eating – but the context transports them elsewhere, representing the dignity of hunger and sharing, the civil strength that arises from the humility of everyday life.

The hand holding out the fork from above, in this context, can be interpreted as a symbol of brotherly help, but also as an iconic and poignant reminder of grace and hope in tragic times.

Dominated by cold, dusty tones, the painting evokes a faded photographic memory, almost like an archive image that has re-emerged from time. The mountain in the background, together with the plume-like clouds, reinforces the sense of an Italy that is wounded but capable of rising again, and the pink accents on the upper edge suggest a balance between melancholy and light.

There is no rhetoric, but rather distilled compassion: painting as an act of memory, but also as a gesture of poetic resistance, a reflection on material and ideal nourishment, an apparently common ritual, a parable on need and dependence.

The work is a tribute to the Cervi family who, on 25 July 1943, on the occasion of Benito Mussolini’s arrest, celebrated by cooking 380 kg of pasta with butter and Parmesan cheese (pastasciutta) for their entire village, Compegine (RE). The seven Cervi brothers were shot by the fascists at the end of that same year, while their father Alcide was arrested. Only two years later, upon his release from prison, did he learn of his sons’ tragic death. He became a spokesperson for the partisan resistance until his death in 1970.